Does the market stability reserve deliver what it promises? An article by Johanna Bocklet and Martin Hintermayer.

The spread of the corona virus is changing people’s everyday lives all around the world. The repercussions of the Sars-CoV-2 pandemic can be observed on the commodity and stock markets worldwide. The effects of the corona crisis can also be seen in the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS). Since the firms in the market need fewer allowances than expected, the crisis will lead to lower emissions in the short term. But emissions could also be reduced in the long term due to the newly introduced Market Stability Reserve (MSR). The crisis could therefore serve as a first test for the MSR mechanism which is the subject of the following short analysis. The analysis shows whether and to what extent the MSR will reduce the emissions that are currently saved due to the corona pandemic also in the long term. that the analysis shows that the reduction depends not only on how severe the crisis will be but also on the behavior of the market participants. In the following, the effects of the corona pandemic on the MSR and the behavior of market participants are analyzed step by step.

What is currently happening in the EU ETS?

Because many companies have cut back or even stopped their production, not only the demand for electricity decreased but also the demand for CO2 allowances in the EU ETS has fallen temporarily. This is particularly noticeable when looking at the development of allowance prices: At the beginning of the year, allowance prices remained at around €24 per tonne of CO2 – roughly at previous year’s mean. With the spread of the corona virus the price fell rapidly; it currently lies at around 16 € per tonne of CO2.

In wake of the corona crisis, companies need fewer allowances than expected to cover their emissions. Despite lower prices, the stagnating economy leads to lower emissions in the short term. This implies that allowances that are currently not used, remain in the market and can be used at a later date. The corona crisis therefore shifts emissions from today to the future. However, due to the fundamental reforms of the EU ETS, only a part of the allowances saved today will still be available in the future. It is difficult to predict today how long the economy will stagnate as a result of the corona crisis. In the reformed EU ETS, however, even a temporary reduction of emissions, will impact aggregated emissions in the EU ETS sectors.

How exactly does the reformed EU ETS work?

The EU ETS currently covers around 45 percent of all European emissions. For every tonne of CO2 equivalent emitted by the industry, electricity and aviation sector, the respective emitting firm has to purchase one allowance (called European Union Allowance). The number of allowances issued per year is limited and is reduced every year so that total emissions in the EU ETS sectors decrease over time.

The European Commission decided to fundamentally reform the EU ETS in 2015 and 2018. The aim was to ensure stable allowance prices-especially in times of crisis- and thus stimulate long-term investment in emission reductions. In particular, the so-called market stability reserve (MSR) and the Cancellation Mechanism were introduced. If firms store a large amount of allowances in their private banks, the MSR reduces the number of allowance to be issued in the following year. The saved allowances are then transferred to the MSR – a kind of public reserve – and partially transferred back to the market at a later point in time. If the volume of the MSR exceeds the auction volume of the previous year, the Cancellation Mechanism renders this allowance surplus invalid from 2023 onwards. Thereby, the reform reduces the size of the ‘temporal waterbed effect’.

Given the current economic situation, what influence do the MSR and the Cancellation Mechanism have on future emissions and prices in the EU ETS?

In the short run, the corona crisis shifts the demand curve of CO2 allowances downwards, as industrial and electricity production in Europe fall. Since the short-run supply remains the same, allowance prices and emissions will fall in the short run. Although companies can sell their unused allowances on secondary markets, it can be assumed that the catch-up effect of the European economy will take some time and emissions overall will be lower this year. This means that a large proportion of the allowances that are temporarily available, will remain in circulation. According to the new regulation, the increase of the Total Number of Allowance in Circulation (TNAC) this year, increases the MSR intake in 2021 by 24% of the 2020 TNAC. Based on the current MSR level, it can be assumed that any further increase in the MSR above the current level will be cancelled in 2023 via the Cancellation Mechanism. Therefore, about one quarter of the emission reduced by the corona crisis will also be saved in the long run.

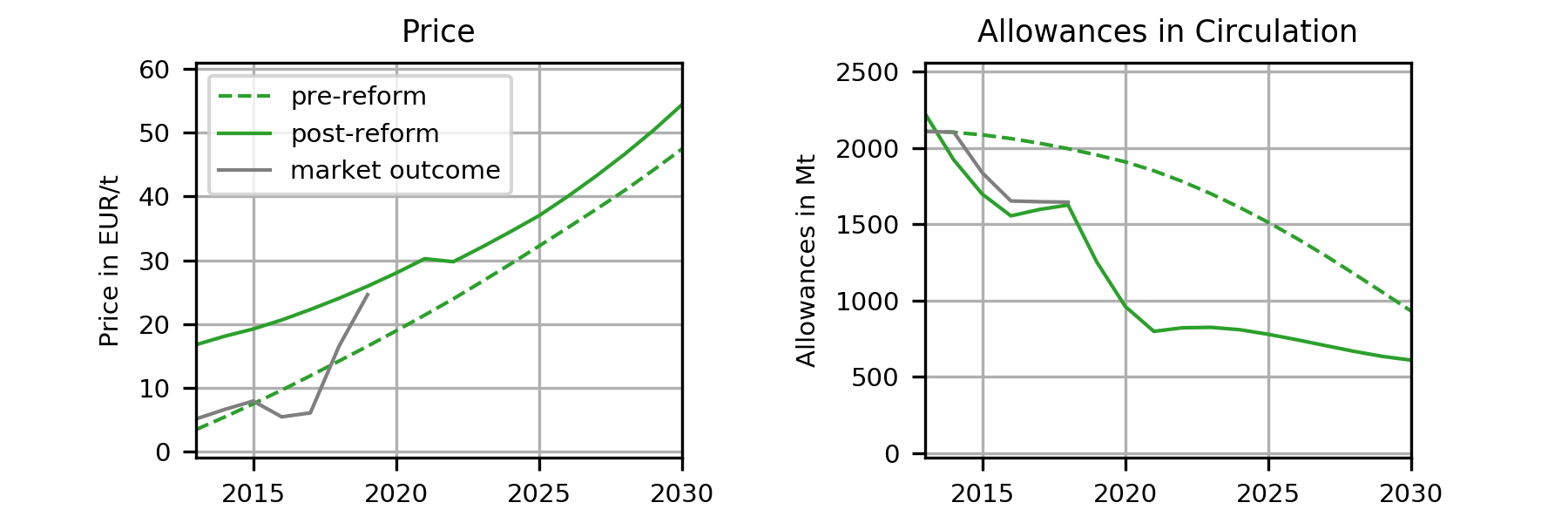

The absolute number of the additional cancellation triggered by the Corona crisis depends on two factors: on the one hand the cancellation volume depends on how strongly the CO2 demand curve described above is shifted by the corona crisis and how long the crisis last. On the other hand, the market outcome (and thus the cancellation volume) is decisively influenced by the behavior and expectations of the market players. Up to now, fundamental models of the EU ETS (cf. Perino and Willner (2016) and Bocklet et al. (2019)) assumed that all market players are fully rational and decide under perfect foresight. However, a new EWI Working Paper (20/01) shows that the real market results in the EU ETS can only be explained if myopia and risk aversion of market participants are taken into account. With their model, the authors Johanna Bocklet and Martin Hintermayer explain the sharp price increase following the reforms and the number of allowances number of allowances in circulation. The results suggest that the participating firms in the EU ETS have an average planning horizon of ten years and reduce price-risk by hedging a part of their emissions already three years ahead.

How does this behavior influence future emissions, prices and the Cancellation Mechanism?

A shorter planning horizon of companies generally leads to higher emissions in the short term and a smaller private allowance bank. The Market Stability Reserve makes this behavior more difficult by shifting part of the allowance supply to the future. The MSR hereby reduces the allowance supply in the short run, so that even highly myopic firms need to abate some of the emissions today. At the same time, myopia reduces the number of allowances cancelled by the cancellation mechanism since the TNAC is considerably smaller. The model of the EWI researcher shows that with an average planning horizon of ten years, only about half as many allowances are cancelled as under perfect foresight.

Hedging, on the other hand, enforces the effects of the reform, as a larger TNAC leads to a larger MSR and thus to additional cancellation. If firms hold enough allowance in their private bank to cover around one year of their emissions, twice as many allowance will be cancelled than without hedging. Further, hedging requirements in addition to the annual allowance cap can lead to a physical shortage of allowance in the short run.

In order to quantify the role of the corona crisis on long-term CO2 savings in the EU ETS, this interaction between the new EU ETS regulation and the behavior of firms in the market is essential. If and how firms change their planning horizons and adjust their hedging strategies in light of the upcoming recession mainly depends on the firm’s expectations of the future economic situation: If companies expect emissions to decrease in the long term, they will adjust their hedging strategy and bank fewer allowances. This reduces the cancellation of allowances and even increase cumulative emissions in the EU ETS. The same applies if companies put more focus on their current economic situation and shorten their planning horizon due to the crisis. However, if the market players in the EU ETS stick to their previous behavior patterns, the MSR can ensure that at least part of the emissions saved today will be permanently reduced, even if an economic catch-up effect will take place in the next years.

The corona crisis can thus be seen as the first test for the Market Stability Reserve. Whether and to what extent the MSR will be able to save the emissions reductions caused by the corona crisis also in the long term, depends in particular on the behavior of the market participants.