In its coalition agreement, the designated German government attributes a central role to the industrial sector in the sustainable transformation of the economy. It wants to introduce suitable instruments such as Carbon Contracts for Differences (CCfDs) to achieve the climate targets. With these special contracts, it intends to promote low-emission technologies – and close the economic viability gap in the basic materials industry. After all, it will take substantial investment to decarbonize the German energy system. For example, in the steel industry alone, there is an investment requirement for hydrogen-based direct reduction of around 8 billion euros by 2030.

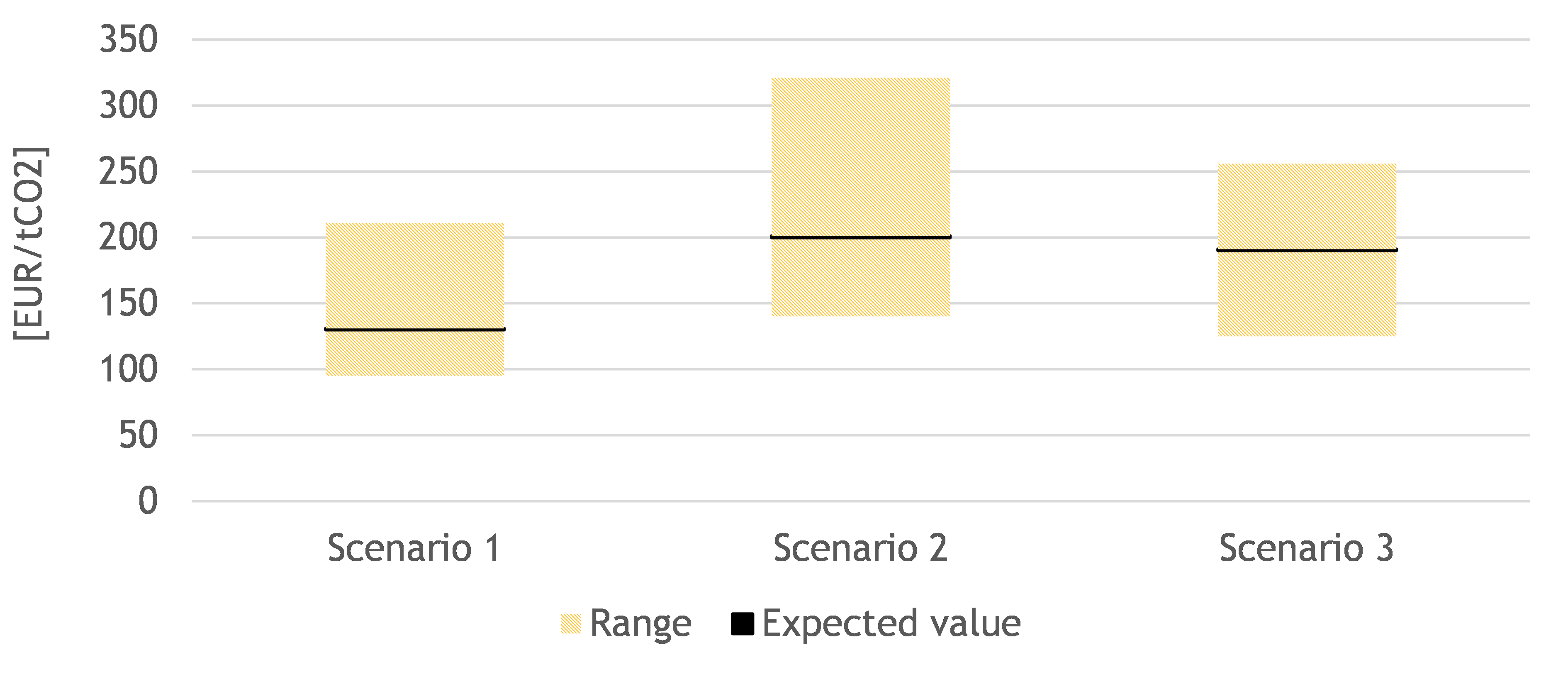

However, whether such investments are profitable is subject to uncertainties. For example, the profitability of low-emission technologies depends on future CO2 prices, as low-emission technologies are only competitive with conventional technologies if CO2 prices are sufficiently high. However, future CO2 prices are uncertain (see Figure 1), and companies can hardly hedge against this.

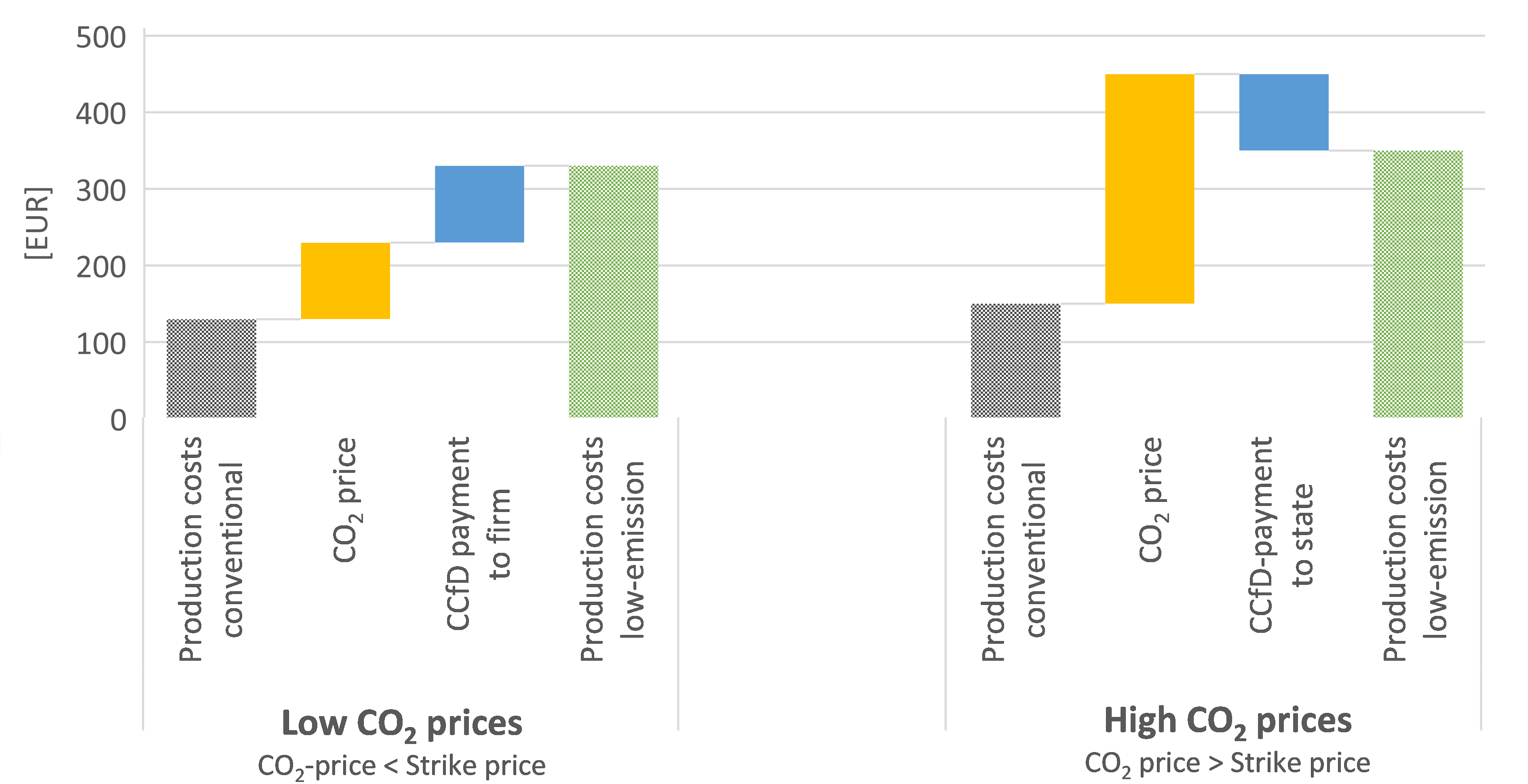

CCfDs are contracts in which the government and a company investing in a low-emission technology agree on a strike price. If the CO2 price is below the strike price, the government pays the difference to the company. If the CO2 price is above the strike price, the company pays the difference to the government. The CCfD thus safeguards the competitiveness of the low-emission technology compared with the conventional production against uncertain CO2 prices: In the event of low CO2 prices, the costs of the conventional production fall and thus the competitiveness of the low-emission technology. Payments from the CCfDs then offset any losses. Conversely, in the case of high CO2 prices, companies have to pay back part of their profits to the state. Figure 2 shows the relationship between revenues, CO2 price and CCfD payment.

EWI experts analytically investigate CCfDs in their working paper “Complementing carbon prices with Carbon Contracts for Difference in the presence of risk – When is it beneficial and when not?”. The research was funded by the Research Programme Hydrogen and the Kopernikus project ENSURE of the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). The analysis shows that the increased security provided by CCfDs encourages companies to invest in low-emission production processes. The increased investments improve welfare if the use of climate-friendly technologies is certainly efficient (i.e., if the variable abatement costs are lower than future CO2 prices). The more risk-averse investors are, the greater the welfare gain from CCfD.

However, for many currently developed technologies, it is uncertain whether the long-term deployment of climate-friendly technology will be efficient later. In these cases, CCfDs carry the risk of keeping potentially inefficient technologies in the market. Such a case occurs when the strike price is higher than the variable abatement cost but later results in a CO2 price that is lower than the variable abatement cost.

There exists the following trade-off: On the one hand, CCfDs motivate companies to invest more in low-emission technologies through their hedging effect, thereby increasing welfare. On the other hand, hedging through CCfDs entails the risk of artificially keeping inefficient production processes in the market at a later stage, which reduces welfare. In this context, the welfare loss increases the higher the probability of promoting inefficient production. Above a certain probability, it makes sense to abandon the CCfD.

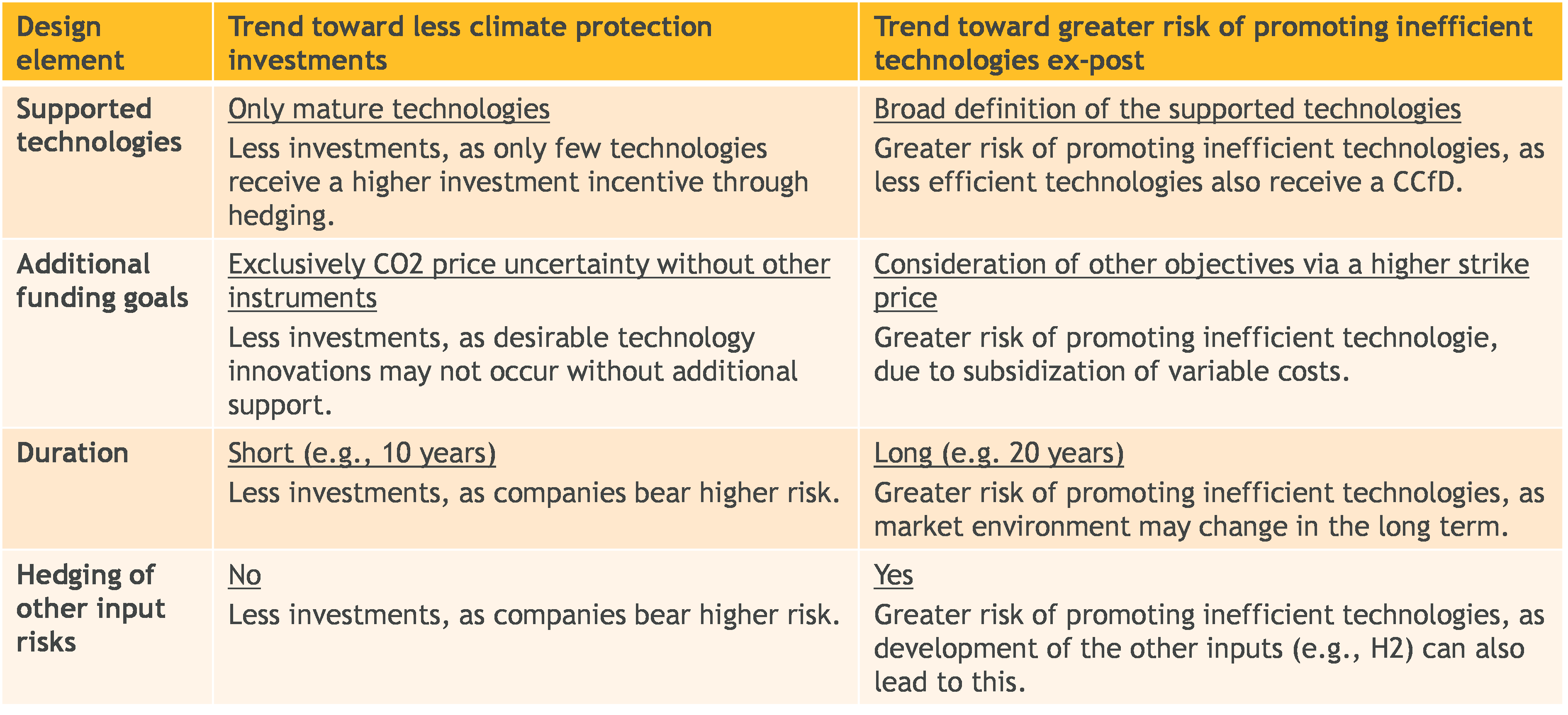

Policymakers should design CCfDs so that the welfare gain from additional investment incentives exceeds the welfare loss from the potential promotion of inefficient technologies. For example, the technology choice affects this trade-off, i.e., which technologies can enter a CCfDs. A too broad choice increases the risk of promoting inefficient technologies in the long run. However, technology selection should not be too narrow so that all necessary investments are incentivized. Table 1 summarizes the implications of different deployment and design options and their impact on the trade-off between investment incentives and efficient production.