February 3, 2020 | Carbon-neutral hydrogen is likely to play an essential role in a decarbonised energy system. However, there is still a lot of research to be done on costs and regulatory requirements. That was the conclusion of a workshop on the topic of hydrogen that EWI organized a few days ago. Around 10 participants from other research institutes as well as from industry and network operators took part in the event.

EWI initiated the “EWI Research Program: The Role of Gas in the Energy Transition” in autumn 2019. As part of the research program, EWI performs and publishes research on gas industry topics. The institute is thus further expanding its gas research expertise. As part of the program, the team led by EWI manager Simon Schulte also trains young scientists with a research focus on gas (especially hydrogen).

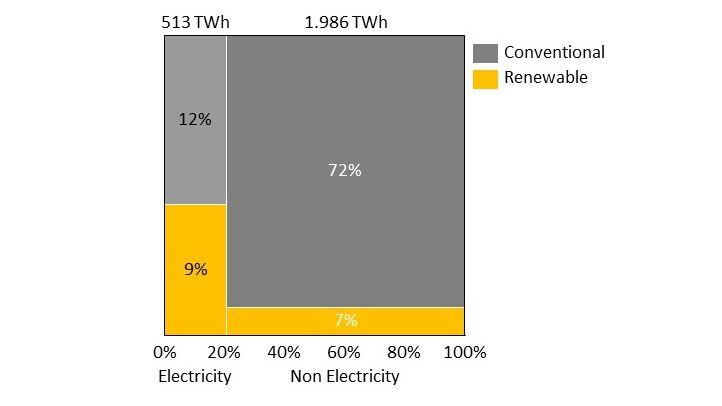

The challenge of decarbonizing the German economy is huge – as was again emphasised by participants at the beginning of the workshop. Figure 1 shows Germany’s 2018 final energy consumption, broken down into electricity on the left and the sum of the other fuels on the right. While renewables already account for 44% of the electricity consumed, their share is less than 7% outside the power sector. Across the entire spectrum, renewables supplied less than a fifth of the final energy consumed. Moving forward it seems unlikely that fossil fuels can be displaced using electricity from renewables alone, given the significant hurdles to their development even today: slow approval processes, NIMBYism and limited domestic potentials. The use of hydrogen as a carbon-neutral alternative will increase accordingly – all participants of the workshop agreed on this.

After that, the focus turned on the costs of carbon-neutral hydrogen production. In a keynote speech, the cost structures of two processes, electrolysis – i.e. the decomposition of water using (green) electricity into hydrogen and oxygen – and the steam reforming of natural gas in combination with carbon capture and storage (CCS), were compared. In steam reforming, natural gas is reacted with steam, producing hydrogen and carbon monoxide, the latter reacting further to carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide is then captured and stored. This option appears to be the cheaper alternative in the short to medium term. But hydrogen generated by electrolysis does have the potential to become competitive in the long term. This depends not only on whether the costs of the technology continue to decrease, but also on the development of electricity and gas prices.

The participants were, however, sceptical that electrolysis can be commercially viable using “excess” electricity from renewables sourced through the grid alone: electrolysers are a capital-intensive technology and thus require high utilization rates to produce hydrogen as economically as possible. Against this background participants raised the question whether a combination of electrolysers with dedicated wind or PV systems makes more sense. In light of the hurdles facing the expansion of renewables in Germany (in particular wind power) the possibility of importing hydrogen from regions with better wind or PV potentials was also raised.

In another presentation, a vision of a European hydrogen transmission, system in which hydrogen is transported from sunny Southern Europe or the windy coasts through pipelines to the industrial centers was laid out. Here, the main question raised was how the existing gas infrastructure could be used most cost-effectively: To what extent could and should existing natural gas pipelines be repurposed and used for hydrogen? And to what extent would it be necessary to invest in network expansion?

How to finance the establishment a hydrogen production and transportation infrastructure is also still unclear. Without a sufficiently high price on carbon, or other types of support, an increase in the use of carbon-neutral hydrogen cannot be expected. However, in order to leverage economies of scale drive down costs through technological learning, it is necessary to advance the uptake of carbon-neutral hydrogen technology. Accordingly, an important question is how to trigger and support this build-out in a cost-effective manner, without the need for open-ended subsidies.

In the second part of the workshop, the regulatory requirements associated with a hydrogen economy were discussed. Incentives are clearly needed to force scaling, promote technological learning and mature the market. But how exactly should economically efficient incentives be structured? The participants made it clear that strategies to avoid a long-term reliance on subsidies need to be considered from the outset. Also debated was whether subsidies and / or support mechanisms should be open to any carbon-neutral hydrogen technology, or whether the targeted support of individual technologies would be more effective.

In building a hydrogen economy, it is important to consider the entire value chain. Here, the roles of existing and new players must be clearly defined. In a mature market, hydrogen would potentially be used in a variety of sectors, including industry, transport, heating and large-scale energy storage. As discussed above, a widespread deployment across many sectors would require the construction of a dedicated hydrogen network, or the repurposing of existing natural gas pipelines. In the latter case, the infrastructure would be owned by the natural gas network operators. How to incentivise and administer the construction and operation of an efficient hydrogen transportation network is an important question. Should gas transmission system operators be responsible for both networks, or should new players operate a separately regulated hydrogen network? Or should hydrogen infrastructure not be regulated at all, at least at first?

The issue of the unbundling of production and transmission was also raised. Who should build and operate the network and who should build and operate, for example, electrolysers? Would having both in the same hands be problematic from an economic point-of-view?

The breadth of content covered at the workshop and the lively discussions have once more shown that there is still much need for research into the economics and the regulatory aspects of a hydrogen economy. With the “EWI Research Programme: The Role of Gas in the Energy Transition” we are devoting ourselves to precisely these and other interesting questions. If you have any questions about the programme, contact the head of our gas team, Dr. Simon Schulte .

Presentations held at the workshop: